India has begun the long and arduous journey to exit the lock-down. Its latest relaxation of restrictions saw masses throng liquor stores even as scores of migrants, who left cities nearly a month ago, finally reached their home states in special trains. These instances have naturally raised concerns of a possible spike in infections amid debates over how the seasonal change would impact the flu — so far, nobody thinks the hot summer months will make a difference to the virus — while Prime Minister Narendra Modi has warned states to be prepared for a possible increase in cases around June-July.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes Covid-19 has no known treatment or vaccine — news of the many trials being conducted and the sleepless nights scientists are putting in to find a drug that will work has made that very clear.But what we do have in our stead is history, for the Covid-19 pandemic isn’t the first we’ve witnessed. Perhaps the best parallel to draw with today is the Spanish Flu, one of the most infamous pandemics the world, and India, saw almost exactly a century ago. And there are important lessons to be learnt from it, especially if there are going be further waves of infections.

A Deadly Beginning

The 1918 influenza pandemic, commonly known as the Spanish Flu, began in Europe towards the end of World War 1. Like Covid-19, it was also a respiratory disease and spread in exactly the same manner as the SARS-CoV-2 virus. It lasted for two years, and infected over 500 million people. This was one-third of the world’s population at the time. It has so far been the deadliest pandemic in history: It is estimated to have killed anywhere between 20 million and 100 million people. In India (then under British rule) alone, it killed over 12 million. The virus that caused the flu was H1N1, the same virus that was responsible for the 2009 swine flu pandemic.

To keep morale up, countries that had been at war, such as the US, UK, France, and Germany, underreported and minimised their numbers through wartime censorship. But the media was free to report about Spain, which had been neutral during the war. This created the impression that the disease hit Spain particularly hard, and thus the name Spanish Flu. Historical epidemiological data is not adequate to pin down the geographic origin or even the time of the pandemic. In fact, many findings have pointed out that the same virus caused small outbreaks in France in army camps with animal farms, months and even years before the pandemic began. The true mortality rate is also unclear due to early fudging of numbers and the rapid decimation of the populations by the virus.

The disease was also oddly more widespread in the summer, whereas influenza cases usually spike in the winter. In India, the disease didn’t affect the British and the privileged much, as they lived in large homes with ample space. But among the rest of the country, there was devastation. Because of shortage of wood for cremation, rivers and drains were filled with bodies. The next year saw a reduction of births by up to 30 per cent, and the resentment against the British during the pandemic is thought to have played a crucial role in stirring up anti-colonial sentiment.

Multiple Waves Of Infections

The biggest contributing factor to the 1918 flu becoming a pandemic was travel across countries, especially of troops. Through the months of April and May of 1918, it spread rapidly in the UK, France, Spain, and Italy. Its mortality rate was roughly similar to the seasonal flu, and the outbreak was relatively mild. Numbers dropped through the summer, but towards late August the same year, a more virulent strain emerged in Europe. Unlike the current SARS-CoV-2 virus, where despite expected mutations there’s no change in virulence anywhere, the mutated strain in 1918 spread like wildfire and wiped out millions. It was suddenly infecting young healthy people too, such as those who served in the war, and killed them within 24 hours.

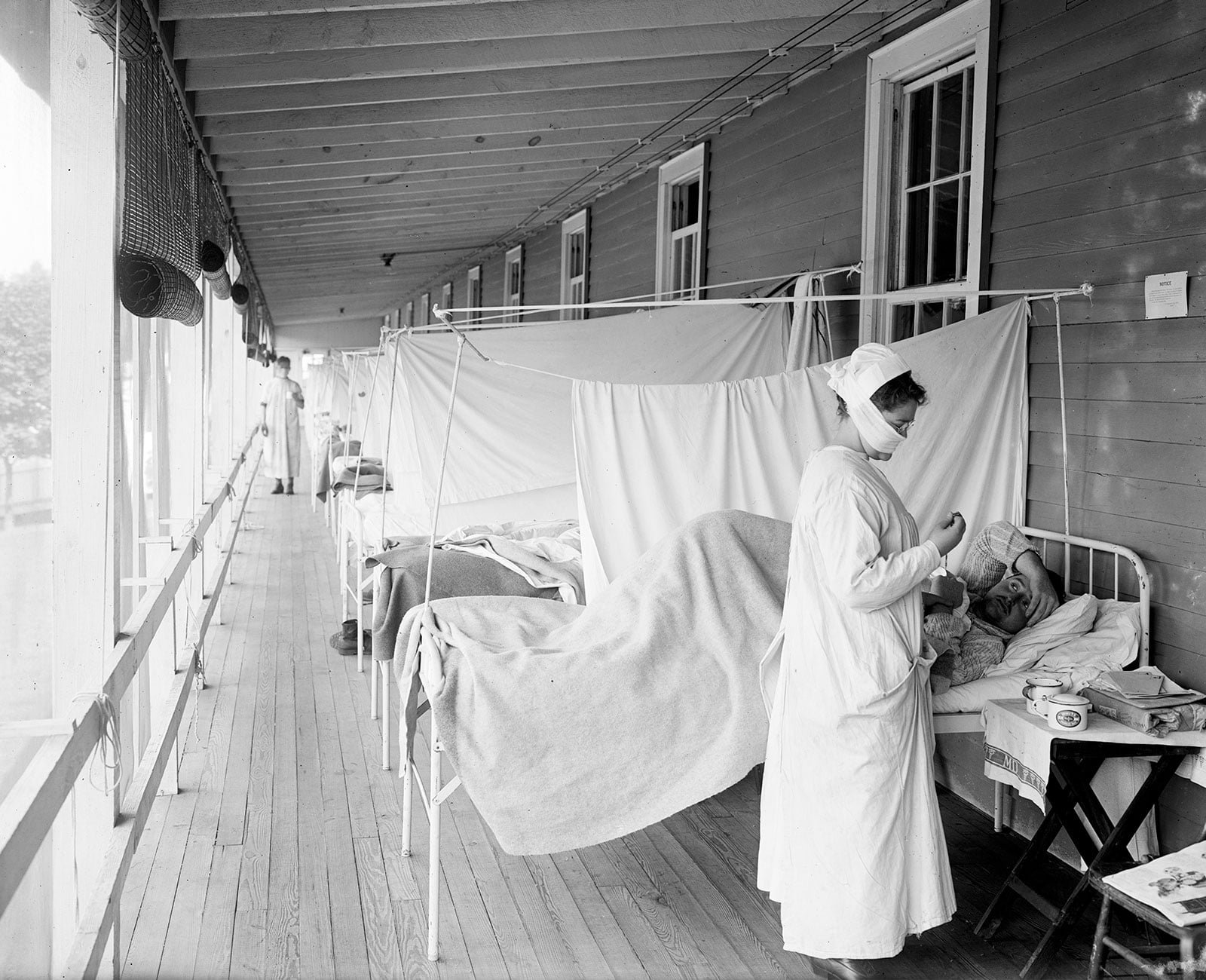

The death rate skyrocketed in two months. Unlike typical illnesses that killed those with inherently weaker immunity — the very young and the very old — this one affected even the strongest of the population. The mechanism behind this was the cytokine storm, which is when the body’s immune system overreacts and kills healthy cells and organs along with the virus. But despite its increased virulence, the rapid spread of the disease was primarily because of a lack of public health systems and the unwillingness of authorities to impose quarantine during wartime. Additionally, hundreds of thousands of healthcare workers were deployed to military camps, leading to severe shortages while treating civilians.

The second wave passed in December of 1918, but a third wave of infections began in January of 1919. The mortality rate was just as high as the second wave, but because the war was over, the disease spread much slowly. A minor fourth wave occurred in the spring of 1920 in certain hot-spots with low mortality. It was likely the virus had mutated into a weaker strain. Influenza viruses are more prone to mutate into more or less deadly strains, unlike corona viruses. The Covid-19 virus too continues to mutate, but a second wave or growth in numbers is not likely to be due to the mutation, but because of lack of appropriate interventions or physical distancing.

What The Past Tells Us

The impact of lock-downs, mandatory masking, and public health interventions, are best documented in America. The US saw its first case on 17 September 1918. In Philadelphia, just 10 days after the first case was reported, there was a parade that was attended by 2,00,000 people. This resulted in the highest death toll in the country. It also saw the highest death rate — 748 people in every 100,000. By contrast, the city of St. Louis, which shut down all public places and started quarantining within two days of the first case, managed to flatten their curve well. The city saw only 358 people of every 100,000 dying.

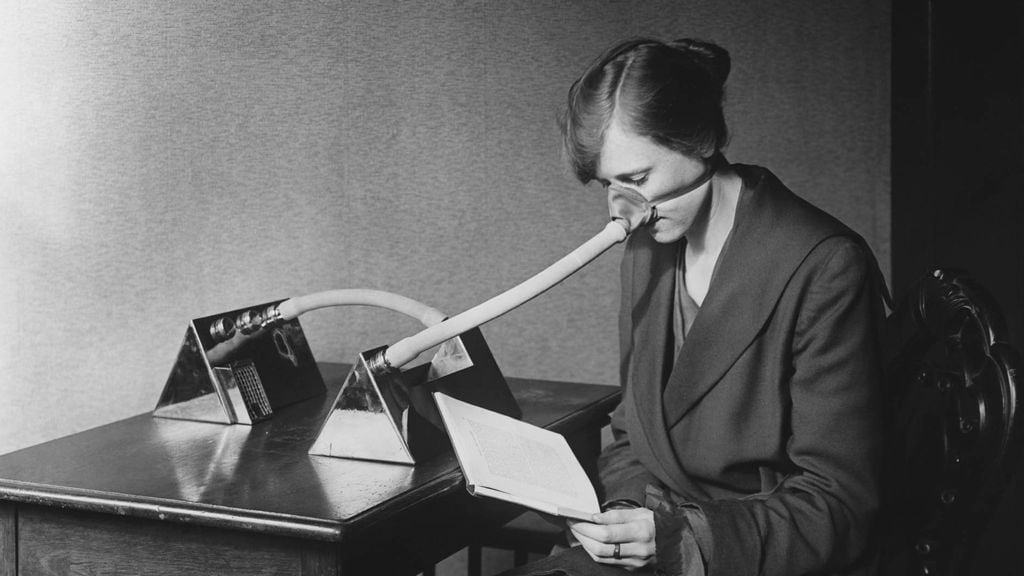

In San Francisco, an ordinance was passed that mandated shutting down of public places, physical distancing, following personal hygiene measures like hand washing, and wearing masks in public. After the first wave passed, there was growing discontent among some members of the public about the strict measures, mainly the mandated use of a mask. Citizens echoed a lot of what the current protesters in America, including billionaire Elon Musk, are saying, such as calling it “unconstitutional” and a violation of rights of freedom. An Anti-Mask League was formed in the city just as it had started to flatten the curve. By the end of October, San Francisco had seen 20,000 cases and 1,000 deaths, but the disease seemed under control. It had been just over a month since the city’s first infection was recorded. Authorities immediately rushed to open up public places, with mandatory masking. Crowds gathered to watch movies and boxing shows but many flouted the mask rule. The Anti-Mask League eventually grew so strong that the city’s mayor gave in and rescinded the masking ordinance on 21 November 1918. All of the public stripped off their masks, despite warnings from the city’s Board of Health, and thronged crowded places. The next wave of the disease hit the city around 7 December 1918, and affected over 45,000 people and killed 3,000 in the city. San Francisco fared the worst among all the places in the US during the pandemic.

Analyses of public health interventions in 43 American cities found that the death rates were up to 50 per cent lower in cities that imposed early measures. The studies also discovered that lifting measures too early can be deadly. Just like San Francisco, St. Louis was confident it had the disease under control and lifted its lock-down after two weeks. An explosion of cases occurred, prompting the city to immediately shut down again.

As India, and other countries feel the pressure to restart their economies again, it is important to note the one thing studies have concluded is the only effective way to flatten the curve and buy enough time to develop a vaccine — persistent physical distancing.